Background Jobs

This article is Part 1 of 2 in the Concurrency in PowerShell series:

- Part 1 - This Article

- Part 2 - Multi-Threading with Runspaces

As the most popular series of posts on my old blog, which also exists as documentation for one of my github projects I thought I’d republish here.

There are three methods to achieve asynchronous processing in PowerShell: background jobs, System.Management.Automation namespace classes, and (coming soon in PoSH v3!) workflows. Workflows actually share characteristics of the other two, but they are different enough to be a new method. I suppose you could also use the System.Threading .NET namespace, but then you’re writing straight .NET code and that’s just cheating. Over the next three weeks, I’ll be posting information about all three of these methods. There will be a lot of information, but it will all be useful and necessary. If you can avoid some of the problems I ran into it will be worth while. I’ll try not to be long-winded, but no promises there.

Before you get started you should know that there are a lot of ‘gotchas.’ Like a lot of PowerShell you’ll come across behavior that isn’t particularly intuitive. There are also a few ways you can get yourself into real trouble. You should familiarize yourself with the concept of thread safety, for example.

The scenario for this series is a common one: I have 50 Excel worksheets that need to be loaded into an SQL Server database as a staging phase for an ETL process. Of course, I could load these one at a time, but depending on how large they are it could take a significant amount of time. Most importantly, I am not fully utilizing the computing resources at my disposal. I want to be to control the amount of resources I use so I can ramp it up for speed if I so desire. One way to do attempt this is through the concurrent processing pattern. Backup jobs are enabled through the use of the *-Job cmdlets and operate very similarly to the forking concurrent process model. Using these cmdlets is straightforward and generally protects you from doing anything particularly harmful, although it isn’t hard to make your computer unusable for a while as I’ll demonstrate shortly.

To get started, I need a data structure for the Excel documents that I’ll be working with as well as a script block to define the work. I’m using a version of some code I posted a while back for this data load task that I have wrapped into a function called Import-ExcelToSQLServer. Note also that this series is based on a presentation I gave at SQL Saturday #111 so you’ll see references throughout this series.

$files = Get-ChildItem '<path>'

$ScriptBlock = `

{

Param($File)

Import-ExcelToSQLServer -ServerName 'localhost' -DatabaseName 'SQLSaturday' -SheetName "SQLSaturday_1" `

-TableName $($File.Name.Replace('.xlsx','')) -FilePath $($File.FullName) -EA Stop

}

Note the properties of the $File object that are being used. Astute PoSHers will note that I’m having to jump through some hoops to get the parameters formatted, which shouldn’t be necessary with System.IO.FileInfo objects. The problem is that though there are System.IO.FileInfo objects in the $Files array the objects only exist in the memory space of the dispatcher process. This means that the new process created by the Start-Job cmdlet has no access to the object across the process context barrier. As a result, the only mechanism available to pass information to the spawned process is through serialization. PowerShell converts the object to XML and then deserializes the XML into an object of type [Deserialized.System.IO.FileInfo] that has a modified set of parameters and only the ToString() method. This is quite frustrating if you are hoping to utilize methods of a FileInfo object, which are no longer available. Not only that, but the overhead of serialization and deserialization is non-trivial, not to mention the overhead of instantiating another FileInfo object if required. On the other hand, the upside is that issues of concurrency control are eliminated and thread safety is guaranteed.

The intention is now to execute the script block for every file in the $files array and I do not want to wait for one to complete before the other begins. So, I can use a foreach loop to execute Start-Job.

Foreach($file in $files)

{

Start-Job -ScriptBlock $ScriptBlock -ArgumentList $file `

-InitializationScript {. Import-ExcelToSQLServer.ps1}

}

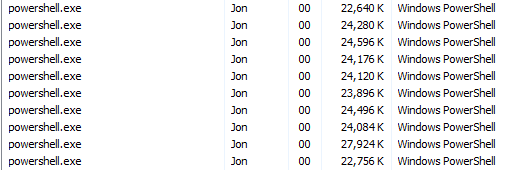

Note the need to include the file containing the function code as an initialization script, even if it is loaded in the host process, due to the process barrier. The new process will, however, execute the PowerShell profile if you have one defined. If you have task manager opened after executing this you’ll see something like this.

A process has been created for each file. The Start-Job cmdlet has also registered handles in the session. These handles are the connection from the host session to the pipeline running in the forked process.

Once the loop exits, control is returned to the host. This is the real intention of the *-Job cmdlets. They allow you to execute work and continue to utilize the shell. The jobs are available to check at the PoSHer’s leisure. If desired, you could use the Wait-Job cmdlet to enter a synchronous state and concede control until the specified job(s) is/are completed.

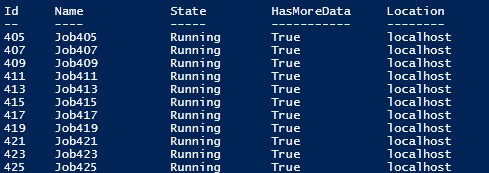

When the time comes, check to see if there are any jobs still running like so.

Get-Job -State "Running"

The Receive-Job cmdlet utilizes the handles registered by the Start-Job cmdlet to access the external process pipelines. Of course, you could provide a single job number or array to Receive-Job. To receive the results of all jobs at one time simply use the pipeline.

Get-Job | Receive-Job

When completed, remember to clear the job-handles.

Remove-Job *

Should I Use Background Jobs?

Fifty running PowerShell processes at ~20MB of memory each (or more, depending on the work), plus the required CPU time (compounded by the need to manage schedulers, etc.) makes for a huge amount of overhead. This results in a run-time that is more than three times longer than executing the tasks synchronously. The individual units of work (one script block execution) needs to be sufficiently long to overcome the overhead of the forked process model.

Significant improvement can be made by throttling the number of processes that are allowed to run at one time. To do so, modify the Start-Job loop like so:

Foreach($file in $files)

{

Start-Job -ScriptBlock $ScriptBlock -ArgumentList $file `

-InitializationScript {. Import-ExcelToSQLServer.ps1}

While((Get-Job -State 'Running').Count -ge 2)

{

Start-Sleep -Milliseconds 10

}

}

The addition of the while loop forces a wait if there are two or more running jobs. This dramatically improves the performance of the process by reducing the amount of overhead at the cost of causing the jobs to essentially run synchronously relative to the dispatching process. Unfortunately, it is still slower than running the jobs synchronously.

Next week I will look at a much more effective method. I am also currently working on a module that will (hopefully) provide a replacement for the Job cmdlets that will operate in essentially the same manner, just much more efficiently. However, it is still important to understand the Job cmdlets if for no other reason than they are on every computer with PowerShell. Additionally, they are simple and perfectly effective in some use cases, such as kicking off a long running process while maintaining control of the shell.